By Bella DiPalermo

When the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) All-Star Dearica Hamby filed a federal lawsuit alleging pregnancy discrimination and retaliation, she did more than bring a personal claim. She revealed a structural tension at the heart of professional sports: the uneasy coexistence between collective bargaining and individual statutory rights. Hamby’s case, which survived the WNBA’s attempt to force it into arbitration, illustrates that not all disputes in unionized sports are swept into the private, insular world of arbitral decision-making. For players, leagues, and unions, the decision carries implications that stretch far beyond one offseason trade.

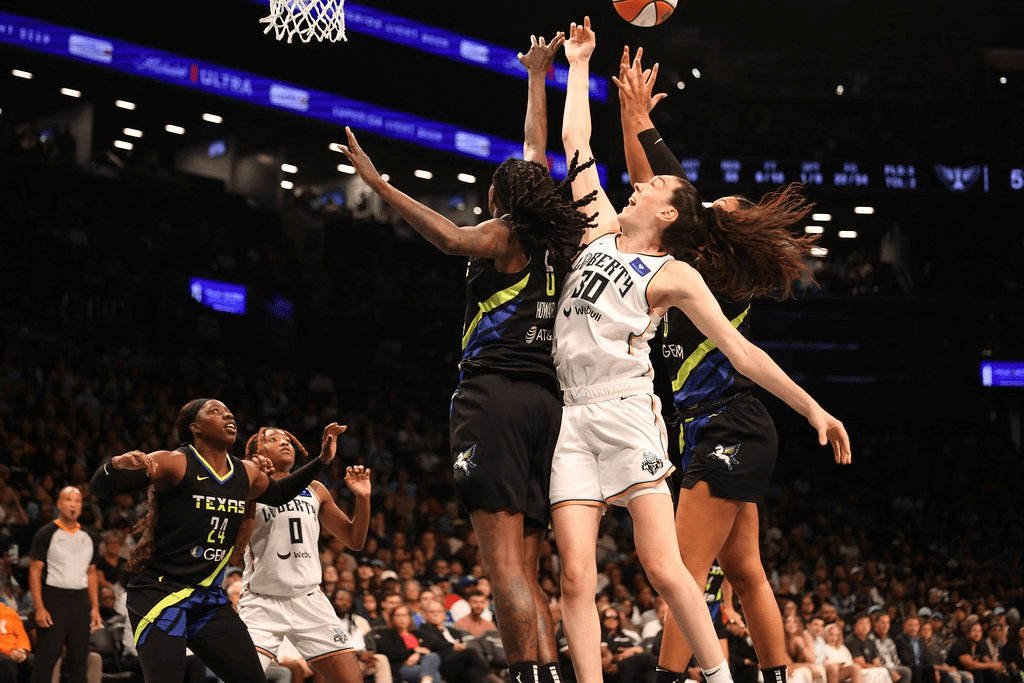

“240822 Liberty_Wings_JohnMc256” by johnmac612 is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Hamby’s suit alleges that the Las Vegas Aces punished her for being pregnant, a violation of Title VII and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. The WNBA argued that her claims belonged in arbitration under the league’s Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA). Yet the court disagreed and stated that a union-negotiated arbitration clause does not automatically waive an employee’s right to litigate federal discrimination claims unless the agreement does so with unmistakable clarity. In Hamby’s case, the CBA lacked such explicit language. This case gives us a way to look at how arbitration works in professional sports and the growing national conversation about worker rights, pregnancy protections, and the role of unions in safeguarding individual statutory claims.

Why Statutory Claims Like Pregnancy Discrimination Are Not Automatically Arbitrated

At first glance, it might seem intuitive that a grievance filed inside a professional sports league automatically would go to arbitration. The WNBA, like the NBA, NFL, and MLB, relies heavily on arbitration to streamline disputes, promote uniformity, and keep sensitive matters out of public courts. But federal law draws a crucial line between contractual disputes and statutory rights. The Supreme Court requires a “clear and unmistakable” waiver before a CBA can force an employee to arbitrate federal statutory claims. This standard emerged most notably in Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp., where the Court held that an employee does not surrender federal civil rights through broad or ambiguous arbitration language.

In applying this doctrine, courts routinely look for explicit references to Title VII, clear waivers of access to judicial forums, or specific provisions stating that discrimination claims must be arbitrated. The WNBA’s CBA does none of this. Its arbitration clause covers disputes arising under the agreement itself, not federal pregnancy discrimination claims. As a result, Hamby retained her right to file suit in federal court. This choice reflects a central principle: statutory protections do not vanish simply because a worker belongs to a union.

How Union-Negotiated Arbitration Differs from Employer-Drafted Agreements

Hamby’s case also illustrates the stark difference between arbitration in union contexts and arbitration in ordinary private employment. In non-union workplaces, employers frequently require workers to sign broad arbitration agreements as a condition of employment. Courts generally enforce those agreements under the Federal Arbitration Act, often compelling statutory discrimination claims into arbitration even when the waiver of rights sits buried in onboarding paperwork.

Collective bargaining operates differently. A union cannot casually waive the statutory rights of all employees. Because a CBA binds every player in the league, federal courts demand heightened clarity before concluding that an entire workforce has surrendered its right to litigate federal civil rights claims. The Supreme Court has made clear that a union-negotiated arbitration clause does not automatically waive an employee’s right to litigate federal discrimination claims unless the agreement does so with unmistakable clarity. In Wright v. Universal Maritime Service Corp., 525 U.S. 70 (1998), the Court held that only a “clear and unmistakable” waiver in the CBA can compel arbitration of federal statutory claims. The Court explained that broad or ambiguous arbitration language is not enough – there must be explicit reference to the statutory rights at issue. Because the WNBA’s CBA did not contain such explicit language, Hamby retained her right to bring her pregnancy discrimination claim in federal court. This protects employees from unknowingly forfeiting vital legal protections and ensures that unions do not unintentionally reduce their own members’ rights. In this way, collective power both expands and restrains arbitration. It creates robust systems for addressing employment disputes, but it cannot quietly override individual access to federal antidiscrimination law.

The Implications for Players’ Rights and League Governance

Hamby’s case signals a broader shift in the legal terrain of women’s professional sports, where issues of pregnancy, gender equity, and athlete autonomy are increasingly visible. For players, the ruling reinforces that collective bargaining does not strip them of fundamental civil rights. While arbitration can efficiently resolve contract-based disputes – salary disagreements, discipline, or trade-related matters – it cannot replace federal protections related to pregnancy, discrimination, or retaliation.

For the WNBA and its teams, the decision highlights the limits of current governance structures. The league cannot rely on the arbitration process to shield itself from judicial review when statutory rights are involved. This marks a meaningful departure from the more insulated disciplinary regimes seen in leagues like the NFL, where arbitration structures are notoriously broad and often upheld. For future WNBA collective bargaining efforts, the Hamby case invites players to seek more explicit protections surrounding pregnancy and parental rights. These topics that have gained momentum as the league expands and female athletes increasingly assert their full personhood, not just their athletic performance, as central to their professional identity. The Hamby lawsuit has already prompted public conversations about whether league policies sufficiently protect players experiencing pregnancy and postpartum recovery. Arbitration clauses, as currently written, do not settle those questions.

A Case Study in Gender Equity and Access to Justice

The Hamby case also arrives at a time when women’s sports are undergoing rapid growth and heightened public investment. With that growth comes scrutiny of how legal frameworks, like arbitration, affect access to justice for athletes facing discrimination. Arbitration is often praised for speed and efficiency, but critics note that it can obscure wrongdoing, limit discovery, and discourage public accountability. These concerns carry weight in cases involving gender discrimination, pregnancy, or retaliation, where transparency is essential to evaluating systemic inequities. By keeping her claims in federal court, Hamby secured a forum where pregnancy discrimination allegations can be addressed openly, with the procedural safeguards that arbitration does not always provide. The decision underscores that arbitration must operate within boundaries, balancing efficiency against the need for public oversight when statutory rights are at stake.

“Arbitration has a vital role in sports governance, but it cannot overpower the fundamental promise embedded in federal law: athletes, like all workers, retain the right to seek justice when discrimination occurs.”

Bella DiPalermo

Conclusion: A Precedent-Setting Moment for Workers in Sports

Hamby’s case is not an isolated dispute between a player and her former team. Rather, it represents a precedent-setting moment in the rapidly evolving legal landscape of women’s professional sports. The ruling affirms that collective bargaining cannot silently waive federal civil rights, reinforces the distinction between contractual grievances and statutory protections, and underscores the role of courts in adjudicating pregnancy discrimination claims. As leagues grow, unions negotiate new agreements, and players advocate for a more equitable sports ecosystem, Hamby’s case will shape the next generation of arbitration clauses. It encourages leagues to revisit contract language, pushes unions to safeguard members’ rights, and reminds players that pregnancy protections are not negotiable. Arbitration has a vital role in sports governance, but it cannot overpower the fundamental promise embedded in federal law: athletes, like all workers, retain the right to seek justice when discrimination occurs.