By Kevin Lauro

Workers make the world go round. They build bridges, fix broken bones, and dispose of trash. Traditionally, we think of the relationship between a worker and their employer as one in which the employer gives the worker a job. However, the employer can also take that job away, but what if the employee is part of a labor union?

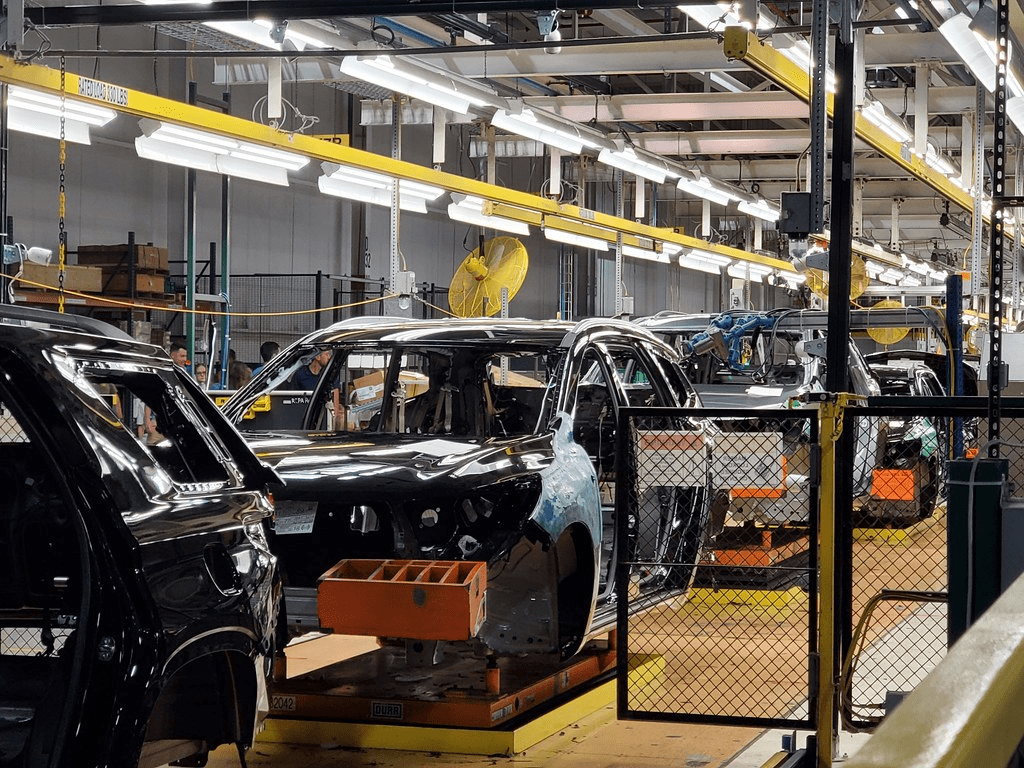

In 2019, General Motors disrupted local communities when it closed its Lordstown Assembly plant in Ohio and two transmission plants in Warren, Michigan, and Baltimore, Maryland, leaving hundreds of workers unemployed. Today, those plants remain closed, and those workers remain jobless. For most American workers, a plant closure and the loss of their jobs would end the story, but that was not the case for these GM workers. Because the employees of the shuttered plants were members of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union and employed pursuant to a collective bargaining agreement, they had additional recourse. Signed in 2015, the agreement prohibited GM from limiting plant activity during its term. The collective bargaining agreement also contained an arbitration clause for resolving disputes between the parties.

Labor unions are a relatively modern invention. Throughout the last 90 years, the UAW has worked to raise wages and increase worker benefits, protect workers from unjust layoffs, and create safer working conditions. The UAW has obtained many of these victories through arbitration. The UAW always bargains for arbitration clauses that permit the union to represent members involved in a dispute. GM and the UAW utilize arbitration clauses to limit litigation costs, shorten the time required to resolve a dispute and build a streamlined process that addresses common issues between the parties.

Following the closure of the plants, the UAW filed a grievance in front of the arbitrator demanding compensatory damages for the laid-off, transferred, or demoted workers. The dispute concerned the following two issues: (1) Whether any worker at the affected plants who accepted employment at another GM facility in lieu of being furloughed was entitled to the retirement benefits offered at their old position, and (2) whether employees who lost wages and other benefits as a result of the plant closures should be compensated for those wages, retirement benefits, and loss of seniority.

The first phase of the arbitration concerned whether the plant closures violated the collective bargaining agreement. The text of the collective bargaining agreement stipulated the identification of any plant closed during the tenure of the agreement before closure. An exception in the agreement allowed GM to close plants when events “beyond the control of the Company” made it impossible to keep them open. GM argued that it did not violate the agreement since the plants were “unallocated” rather than closed. GM also argued that even if it did close the plants, the market decline made it impossible for it to continue to operate the plants any longer. The UAW countered that even if conditions had made it more difficult to operate the plants, the market allowed these plants to remain open for the remainder of the collective bargaining agreement’s term.

The arbitrator decided that GM’s creative use of the term “unallocated” to describe the plant closures did not change the reality of their actions, that they had closed the three plants. The decision also noted that “financial imperatives, inefficiency, and impracticality simply are not synonymous with the more stringent standard of . . . impossibility.”

“Traditionally, we think of the relationship between a worker and their employer as one in which the employer gives the worker a job. However, the employer can also take that job away, but what if the employee is part of a labor union?”

Kevin Lauro

The second phase of the arbitration focused solely on the financial compensation owed to the affected workers and, if so, how much. The dispute focused on money owed, which workers were eligible for an award, the amount of owed pension contributions, and whether the workers should have received the standard ratification bonus paid out to members upon executing a new collective bargaining agreement. The UAW argued that affected workers should receive back pay for their straight wages and projected overtime following the closures. The UAW also argued that the affected workers should receive credit for time worked towards raises and vacations, reimbursement for insurance and retirement contributions, and the distribution of the lump ratification bonus to all UAW workers following the ratification of the 2019 collective bargaining agreement. GM argued the restriction of the number of eligible employees under the agreement and the amount of lost wages and benefits. The arbitrator ultimately awarded 797 affected workers nearly $8 million. This award included lost wages (including overtime), 401k and pension contributions, and performance bonuses but not the $11,000 ratification bonus.

While failing to reopen the plants, this arbitration award offered a partial remedy to the UAW members who lost their jobs. While not perfect, the award these workers received, which averaged around $10,000 per worker, was only possible through the collective power of a union arguing, negotiating, and arbitrating on their behalf.