By: Aissatou Toure; Articles editor

Arbitration is in demand. In 2023 alone, complainants brought 7,554 new cases into arbitration. Before becoming an arbitrator, one must know what arbitration entails; however, arbitration evades easy definition. The World Intellectual Property Organization defines arbitration as: “a procedure in which a dispute is submitted, by agreement of the parties, to one or more arbitrators who make a binding decision on the dispute.” In other words, arbitration consists of a middle ground that offers two parties an opportunity to resolve issues and disputes without bringing them up to trial. It is private, which allows parties to address disputes without fear of public judgment. Arbitration can often be cheaper and faster than litigation as well. Arbitration works as a form of dispute resolution, often bundled, and confused with mediation. Arbitration differs from mediation in that arbitration renders a verdict whereas mediation aims for cooperation and understanding of key issues. Mediation also focuses on understanding the other side’s perspective when reaching an agreement. Another key difference is that arbitration has an arbitral panel. Mediation, on the other hand, usually has a third-party mediator and can be done with only the mediator and the clients. These two terms are often mistaken for each other, creating another obstacle when recruiting new arbitrators.

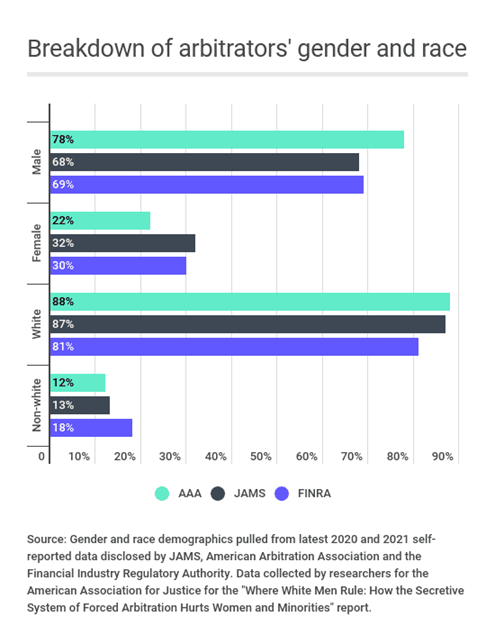

So how does one become an arbitrator? Each state’s requirements vary, but most states at a minimum require a bachelor’s degree. However, despite the minimum requirement, most arbitral institutions require further qualifications. For example, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) requires two years of college-level credit and five years of paid work experience. On the other hand, JAMS (formerly known as the Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services) looks for arbitrators with significant alternative dispute resolution experience. Finally, the American Arbitration Association (“AAA”) requires a minimum of ten years of senior-level business or professional experience or legal practice. Therefore, a logical possible course of action is to start at FINRA until you have enough experience to join JAMS and finally end up in AAA. Regardless of the strict minimum requirements, there remains a disproportionate number of male arbitrators practicing in the field.

A clear disparity in age exists as well. In total about 63% of arbitrators are above the age of 50 and in 2020 the average age for arbitrators appointed to the ICC was 56. The high average age causes concern, now that arbitration has entered into a modern age, where approaches lean more heavily toward increasing diversity and Environmental, Social, and Governance (“ESG”) in the field. The new landscape is causing a rapid change in disputes and awards. To solve these new disputes, a more diverse panel of arbitrators can fully understand and provide new perspectives on the issue. The absence of diversity in the arbitration field remains puzzling, especially considering that the minimum requirement is usually a bachelor’s degree. Clients are also exerting significant pressure for increased diversity in the field and the creation of a more accurate representation of their interests.

Becoming a competitive arbitrator as a person who is non-white, female, and under the age of fifty seems difficult but not impossible. There has been a push for diversification of the arbitration field since 2018 that has been largely unsuccessful due to what Professor Catherine Rogers calls the “Arbitrator Diversity Paradox.” Professor Rogers argues that the increased global concern about the absence of diversity in arbitration has failed to translate those concerns into solutions. Professor Rogers believes that the idealistic goal of increasing gender diversity fails with a lack of actions and “willingness” to act to ensure the goal. The more difficult the goal, the less likely others are willing to work to achieve it. Another issue is incumbency. According to the 2020 ICC statistics, there were 1,520 confirmations in total. Of those individuals confirmed, 66% were confirmed for the first time and 34% were confirmed in the past. For a position with term limits, the fact that one-third of confirmations are incumbents creates an obstacle for diversity in arbitration. While the push for diversity continues, the arbitrator requirements are increasing. The answer to the absence of diversity in arbitration lies in changing the standards set by the institutions. One way that the International Court addresses the issue of the lack of diversity in arbitration is by (1) encouraging the appointment of new young arbitrators for less complex cases or cases involving relatively low amounts in dispute and (2) favoring gender diversity.

The absence of diversity in the arbitration field remains puzzling, especially considering that the minimum requirement is usually a bachelor’s degree. Clients are also exerting significant pressure for increased diversity in the field and the creation of a more accurate representation of their interests.

Aissatou Toure

The first suggestion by the International Court is a great answer to the lack of young arbitrators. Allowing new and young arbitrators to start with a lighter load parallels the practices of many other industries with entry-level positions. This provides opportunities for appointees to handle the complicated nature of arbitration and gives them the experience needed for competition in arbitral institutions. This also applies to those people who are new to the field of arbitration generally. By allowing a system that allows interested appointees to arbitrate without having vague, complicated criteria that ultimately discourage them from applying, we create more opportunities and diversify the arbitration field both domestically and internationally.

The second suggestion by the International Court works only as a temporary solution and may cause more dissent from other arbitrators. Creating a quota remains difficult to implement in the long run because it can cause distrust and resentment without actually changing the specific cultural beliefs and attitudes that created such a disparity in the first place. There that are instances, however, in which quotas offered effective positive change. Creating quotas at the top managerial and executive levels has successfully expanded institutional diversity. This allows the introduction of diverse candidates at the decision-making level who can perpetuate future positive and diverse changes. However, it is important to remember that diversity is the first step. Inclusion is just as an important, if not more so, goal to accomplish.